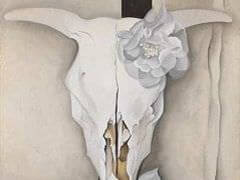

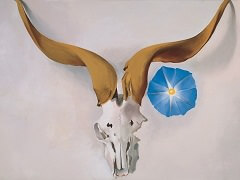

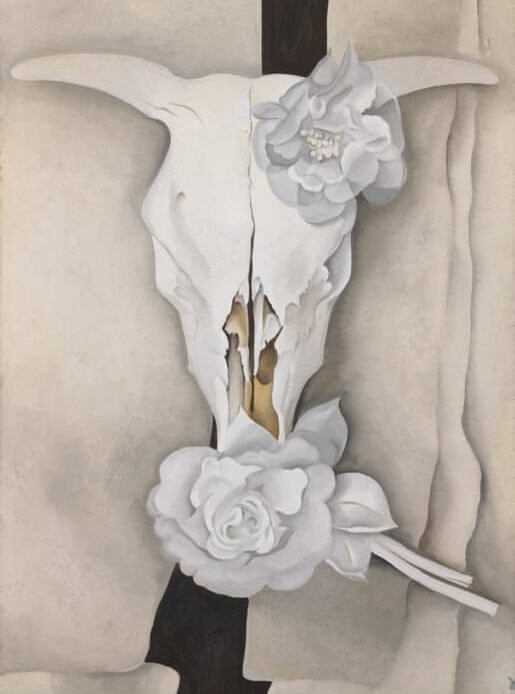

Cow's Skull with Calico Roses, 1931 by Georgia O'Keeffe

Over the years, O'Keeffe became an anti-authoritarian revolutionary, the notoriety of her lifestyle sometimes overcoming the originality of her work. She shunned European traditions and influence and resisted all manner of paternalism.

Like Piet Mondrian, she never signed her paintings, and like Jackson Pollock, she found Native American art as inspiring as Renaissance

art. Eventually, she abandoned the New York City art scene that founded her reputation and moved west to New Mexico for a more authentic artistic experience. There, in a landscape unencumbered by undue neighborliness and

excessive vegetation, she created work that was timeless, universal, and impersonal.

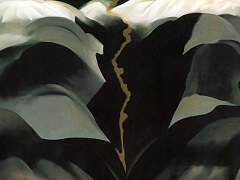

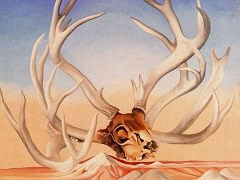

The rugged mountain terrain with its fossilized formations, saturated color, and naked wilderness held an inexhaustible fascination for O'Keeffe and was a source of inspiration for most of her artistic career.

GeorgiaO'Keeffe said of the sun-bleached bones and skulls she found in the desert:

To me, they are as beautiful as anything I know. To me, they are strangely more living than the animals walking around. The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even though it is vast and empty and untouchable and knows no kindness with all its beauty ”

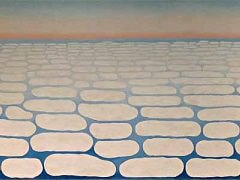

From the grandeur and vastness of the western landscape, O'Keeffe extracted a compressed, concise, and reductive style. Breaking away from the constraints of scale, she painted telescopic images that favored the distant and the immediate.

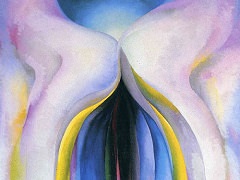

She made the small seem large and the large small as she focused on a single isolated object: a mountain, a stone, a flower, a bone. Educated in oriental scroll painting and influenced by the work of

Wassily Kandinsky, she understood that emptiness could signify fullness, and she applied that principle in panoramic landscape paintings, as well as in lone objects placed in pictorial space.

Like Frida Kahlo, with whom she maintained a lively correspondence, O'Keeffe became intimately familiar with her subjects, wanting to merge and become one with them at the moment of creation. "I find

that I have painted my life" she confided, "things happening in my life - without knowing". Close acquaintance with the subject guided the accurate presentation not only of the outward image but also of the sensation within, transforming

the subjective and personal to the mystical and universal.